>

Native Americans, in addition to the southwestern tribes, utilize kachina dolls to a lesser

extent. The Seneca use dolls in divination (Dream Divining). The Nooksack consider a person's

soul to look like a doll (sitec) image of him or her. Wanagemeswak (Penobscot) are dwarfs that

leave lucky dolls to be found by people. A Pequot woman used a doll to overcome a giant. The

Tlingit hold that sickness is caused by witches, who use dolls to inflict it.

The Seminole of Oklahoma and Florida used clay human effigies to avenge murders. Four male

relatives of a homicide victim participated in this ritual. The doll maker, joined by the other

three men, placed the doll in the center of a hot fire. If the clay figure fell over as it turned

red, the murderer would die in four days. If the effigy remained erect, the murderer had

strong counter-powers and would probably become ill but not die.

Kachina Dolls and The Hopi Native American

The Hopi Native American Tribe has always valued kachina dolls because kachina spirits are

extremely important to their evryday life. Kachina dolls are made in the image of various

kachina spirits which the Hopi worship.

The kiva has been at the heart of Hopi tradition for over one thousand years. Kiva ceremonies

take place in sacred, round ceremonial chambers. Hopi Native Americans believe life began in

the kivas. The Hopi believes that first people to live on earth left their dark home in the

earth's interior and climbed from the kiva upward toward the light and the present world.

They also believe they will return to the underworld after death.

Kachinas were the spiritual beings who taught the Hopis how to live on earth after their

emergence. The kachina dolls are religious icons. They represent the spiritual essence of

everything in the world. In a way they're like statues of saints. The word "Kachina," Katsina

or Qatsina, means "life Bringer," in the Hopi language.

Among the Native American tribes like the Zuni, Apache and Hopi living in the Pueblos of the

Southwest, the rain deity kachina is a spirit who is responsible for their survival. Without the

kachinas help, water in the rivers will not flow and the crops will not be abundant.

Native American kachina carvers use cottonwood root, which is carved and painted to

represent objects from Hopi spiritual beliefs.

As far back as the 16th century, the Spanish wrote about seeing bizarre images of the devil,

most likely kachina dolls, hanging in Pueblo homes. Older style kachinas are usually adorned

with fur, bird feathers, turquoise and other natural elements to make them look realistic.

The first kachina doll was collected from the Hopi in 1857 by Dr. Palmer, a U.S. Army surgeon.

He presented it to the National Museum. Military men and government agents were

fascinated by the dolls from the beginning. Unfortunately, the Hopi sold them.

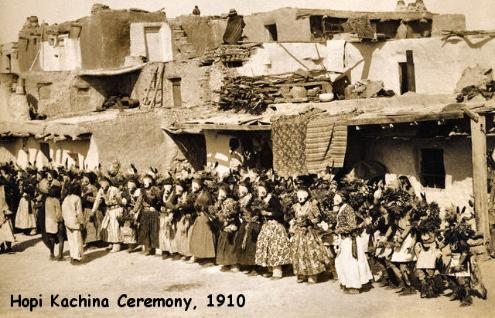

Southwestern Kachina Rituals: Plaza Dances

Public kachina dances performed in village plazas during the spring and summer months,

culminating a longer series of secret or private rites. These events are sponsored to

celebrate a special event and include feasting and socializing, as well as dances that both

entertain and enact Hopi religion. The dances are unquestionably religious in character,

presenting kachinas and emphasizing fertility, rain, health, and life. These dances are either

mixed dances, where each dancer presents a different type of kachina, or line dances, where

all the dancers present the same kachina. Clowns often perform during the dances, especially

in the intervals between kachina dance sets.

Heluta is father of the kachinas, creator of deer; he lives in Shipap. As father of kachinas he

is first to appear at kachina dances, announcing the kachinas to the people by means of signs.

Heluta is a figure in many stories.

In the antelope dance there is a transition to the purely demoniac kachina dances, the chief

task of which is to pray for a good crop harvest. In Oraibi, for example, there exists still

today an antelope clan, whose chief task is weather magic.

Whereas the imitative animal dance must be understood in terms of the mimic magic of

hunting culture, the kachina dances, corresponding to cyclic peasant festivals, have a

character entirely of their own which, however, is revealed only at sites far removed from

European culture. This cultic, magical masked dance, with its entreaties focused on inanimate

nature, can be observed in its more or less original form only where the railroads have yet to

penetrate and where—as in the Mold villages—even the veneer of official Catholicism no

longer exists.

The children are taught to regard the kachinas with a deep religious awe. Every child takes

the kachinas for supernatural, terrifying creatures, and the moment of the child's initiation

into the nature of the kachinas, into the society of masked dancers itself, represents the

most important turning point in the education of the Native Americans,

Winter solstice ceremony. The Hopi Ritual Cycle is an annual cycle divided roughly in half. The

period beginning with the winter solstice and lasting until a few weeks past the summer

solstice is distinguished by the frequent appearance of kachinas, masked messenger spirit

beings.

Soyal is a winter solstice ritual designed to turn the sun back in its course. Combined with

this may be a ritual in which medicine is prepared and either drunk or rubbed on the body to

promote health and strength. The first kachina to appear, thereby opening the kachina season,

is Soyal, a shabbily dressed figure who totters along in the movements of an old man. He

makes his way to kivas, placing prayer feathers (paho) and sprinkling cornmeal. Other Soyal

actions include the preparation of prayer feathers for relatives, crops, animals, houses, cars,

and personal well-being.

Hopi Niman Ceremony

The Niman Ceremony, also called the Home Dance, is the last appearance of kachinas at Hopi

before they depart for their homes in the San Francisco Mountains. This early August event

closes the kachina season. The most common masked dancers on this occasion are the Hemis

kachinas, although others may appear. In its solemnity, this kachina dance differs from the

plaza dances that precede it throughout the spring and summer. No clowns are

present.

Kachinas and Kachina Dolls- Their Meaning to the Tribes

Corn Maiden Kachina Doll

Corn woman or maiden who is a figure in many stories. She may appear as a kachina mana, that

is, a female kachina. At Cochiti, for example, Yellow Woman kachina wears a green mask and

has her hair done in butterfly whorls on the sides of her head. She wears an embroidered

ceremonial blanket as a dress and an all-white manta over her shoulders. Yellow Woman tends

to be a stock heroine in many stories, taking on a wide range of identities, including bride,

witch, chiefs daughter, bear woman, and ogress.

Sun Kachina and Corn Maiden Dolls

A despised boy who claims to be the grandson of Paiyatemu, the sun youth kachina, is tested

by his father. As a reward for passing the tests, he is given the power to marry the

daughters—Corn Maidens—of eight rain priests. The powerful songs known by these Corn

Maidens cause so much rain that it floods, and the people retreat to Corn Mountain.

The flood finally stops when the young son and daughter of the village chief are sacrificed.

Dressed in ceremonial costume and carrying great bundles of prayersticks, they step off the

mesa into the flood—the boy to the west, the girl to the east. They become the Boy and Girl

Cliffs of Corn Mountain, the place of a shrine considered to give blessings in conception and

childbirth.

Kokopelli Kachina Doll

The Humpbacked Flute Player who appears widely in rock art and ancient pottery throughout

the southwestern United States. Often humpbacked, carrying a flute, and ithyphallic, this

figure has become a widely used motif on pottery, jewelry, and other Native American items.

Although his origins and the significance of his prehistoric appearances are speculative, he has

contemporary presence as a figure in Hopi stories and as a Hopi kachina, where he is

characterized as a seducer of girls, a bringer of babies, and a hunting tutelary.

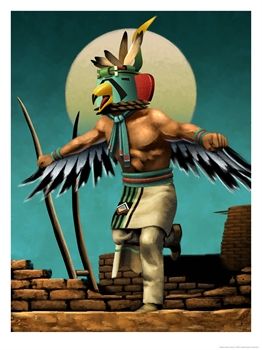

Heluta Kachina Doll

Heluta is father of the kachinas, creator of deer; he lives in Shipap. As father of kachinas he

is first to appear at kachina dances, announcing the kachinas to the people by means of signs.

Heluta is a figure in many stories.

Kobictaiya Kachina Doll

These are the powerful spirit beings similar to kachinas. A story tells how it was determined

that they would never know sexual intercourse. The daughter of a war chief dies. Her body is

stolen by witches (kanadyaiya) who revive her in order to seduce her. The Kobictaiya come to

her rescue.

Rather than fight for her, they decide to play a game with the witches. If the witches win,

they will get the girl to use as they desire. If the Kobictaiya win, they get the girl but must

forgo sexual relations forever. The Kobictaiya are the victors.

The Kobictaiya appear in masked personated form only at the winter solstice ceremony,

during which they promote fertility and aid the sick. They live either in the east at the

sunrise or in a crater southeast of Acoma.

Pautiwa- Zuni Chief Kachina Doll

Pautiwa, chief of kachinas, summons people from Zuni to Kachina Village to gamble with the

kachinas. They bring goods with them to stake on the game. The kachinas win, and the six men

who lose are trapped under the floor. Realizing that anyone else who loses to the kachinas will

become trapped also, the people send a young man, despised by all, to gamble with them. They

consider his loss of no consequence. However, the despised young man has allied himselfwith

Spider Woman by giving her an offering. He challenges the kachinas and, with Spider Woman's

help, wins every time. At each loss, one of the kachinas drops beneath the floor. The kachinas

soon stop gambling and pay in deer for their losses. They

Soyok Kachina Doll

A ritualized frightening by horrible-looking kachina figures (Soyok) in an effort to discipline

naughty children. The event occurs during Powamu. Upon a parent's request, several of these

ogre figures appear at the home of the naughty child. They demand impossible tasks of the

children, warning them they will be back to check on them in several days. Of course, when

they return the children have not accomplished the assigned tasks and are usually hiding

somewhere in the house. The parents present the children to account for their actions.

The Soyok kachinas, hideous in appearance and equipped with cleavers and saws, demand that

the child be turned over to be eaten. The parents refuse to release the child, but the process

ends up costing the family all its stores of food. The Soyok kachinas, loaded with food, host a

feast for the community and, it is hoped, the child's behavior improves.

Native American Zuni Kachina Dolls

A group of kachinas who live to the south of Zuni and are the enemies of the kachinas who live

at Kachina Village. The hunting territories of these groups overlap. The Kanaakwe decide to

conceal all the deer by hiding them in their corrals. The kachinas of Kachina Village hunt

without even seeing any game. Learning that the deer have been concealed, they challenge the

Kanaakwe to a fight over hunting rights.

The Kanaakwe string their bows with yucca fiber, while the kachinas string theirs with deer

sinew. When it rains, the deer sinew stretches while the yucca fiber tightens, enabling the

Kanaakwe to be victorious. As a result, the deer belong to the Kanaakwe, who are responsible

for bringing them to the Zuni people, while the kachinas of Kachina Village bring the Zuni

people corn, seed, and other things.

This story is often included in the stories of Zuni Emergence. In some versions the Kanaakwe

are led by a giantess who keeps her heart in a rattle. Other versions account for the

origination of the Ahayuta, the twin warrior sons of the Sun Father (Yatokka taccu), in

response to the Kanaakwe concealing the deer. In some versions, the sons travel to their

father to obtain weapons to kill the giantess leader of the Kanaakwe.

Rain priests are associated with each of the six directions, that is, the four cardinal

directions plus zenith and nadir. They live on the shores of oceans and in springs. They come to

Zuni on the winds in the form of clouds, rainstorms, fog, and dew.

Pautiwa, chief of kachinas, summons people from Zuni to Kachina Village to gamble with the

kachinas. They bring goods with them to stake on the game. The kachinas win, and the six men

who lose are trapped under the floor. Realizing that anyone else who loses to the kachinas will

become trapped also, the people send a young man, despised by all, to gamble with them. They

consider his loss of no consequence. However, the despised young man has allied himself with

Spider Woman by giving her an offering. He challenges the kachinas and, with Spider Woman's

help, wins every time. At each loss, one of the kachinas drops beneath the floor.

The kachinas soon stop gambling and pay in deer for their losses. They tell the people that the

six men they have lost will remain at Kachina Village. The people discover that mist and fog

come from the place where the lost men sit. The men tell the people they have become Rain

Priests. Whenever the people want anything they are to come and make prayer offerings, and

the Rain Priests will help them.

In accounting for the origin of the Rain Priests, this story explains why the men who personify

the Rain Priests go on pilgrimage to the lake under which Kachina Village lies, and why people

go to Kachina Village upon death.

The rites that initiate Pueblo children into their adult religious lives include the revelation

that kachinas are humans wearing masks. This often-disenchanting experience is conjoined

with the demand that initiated youth not reveal this knowledge to the uninitiated. Stories of

what might happen to them if they tell are related to reinforce the importance of keeping

this initiation secret.

The Zuni tell a story set at the time during the flood when the people are living on Corn

Mountain. An initiation is held and the initiates warned against telling the secret. While playing

at making clay figures of kachinas, one youth reveals that the kachinas are the children's

fathers and uncles dressed up in masks. Dangerous kachinas are summoned. They break open

the boy's house where he is hiding, cut off his head and, leaving the body lying in his house,

kick his head all the way to Kachina Village.

extent. The Seneca use dolls in divination (Dream Divining). The Nooksack consider a person's

soul to look like a doll (sitec) image of him or her. Wanagemeswak (Penobscot) are dwarfs that

leave lucky dolls to be found by people. A Pequot woman used a doll to overcome a giant. The

Tlingit hold that sickness is caused by witches, who use dolls to inflict it.

The Seminole of Oklahoma and Florida used clay human effigies to avenge murders. Four male

relatives of a homicide victim participated in this ritual. The doll maker, joined by the other

three men, placed the doll in the center of a hot fire. If the clay figure fell over as it turned

red, the murderer would die in four days. If the effigy remained erect, the murderer had

strong counter-powers and would probably become ill but not die.

Kachina Dolls and The Hopi Native American

The Hopi Native American Tribe has always valued kachina dolls because kachina spirits are

extremely important to their evryday life. Kachina dolls are made in the image of various

kachina spirits which the Hopi worship.

The kiva has been at the heart of Hopi tradition for over one thousand years. Kiva ceremonies

take place in sacred, round ceremonial chambers. Hopi Native Americans believe life began in

the kivas. The Hopi believes that first people to live on earth left their dark home in the

earth's interior and climbed from the kiva upward toward the light and the present world.

They also believe they will return to the underworld after death.

Kachinas were the spiritual beings who taught the Hopis how to live on earth after their

emergence. The kachina dolls are religious icons. They represent the spiritual essence of

everything in the world. In a way they're like statues of saints. The word "Kachina," Katsina

or Qatsina, means "life Bringer," in the Hopi language.

Among the Native American tribes like the Zuni, Apache and Hopi living in the Pueblos of the

Southwest, the rain deity kachina is a spirit who is responsible for their survival. Without the

kachinas help, water in the rivers will not flow and the crops will not be abundant.

Native American kachina carvers use cottonwood root, which is carved and painted to

represent objects from Hopi spiritual beliefs.

As far back as the 16th century, the Spanish wrote about seeing bizarre images of the devil,

most likely kachina dolls, hanging in Pueblo homes. Older style kachinas are usually adorned

with fur, bird feathers, turquoise and other natural elements to make them look realistic.

The first kachina doll was collected from the Hopi in 1857 by Dr. Palmer, a U.S. Army surgeon.

He presented it to the National Museum. Military men and government agents were

fascinated by the dolls from the beginning. Unfortunately, the Hopi sold them.

Southwestern Kachina Rituals: Plaza Dances

Public kachina dances performed in village plazas during the spring and summer months,

culminating a longer series of secret or private rites. These events are sponsored to

celebrate a special event and include feasting and socializing, as well as dances that both

entertain and enact Hopi religion. The dances are unquestionably religious in character,

presenting kachinas and emphasizing fertility, rain, health, and life. These dances are either

mixed dances, where each dancer presents a different type of kachina, or line dances, where

all the dancers present the same kachina. Clowns often perform during the dances, especially

in the intervals between kachina dance sets.

Heluta is father of the kachinas, creator of deer; he lives in Shipap. As father of kachinas he

is first to appear at kachina dances, announcing the kachinas to the people by means of signs.

Heluta is a figure in many stories.

In the antelope dance there is a transition to the purely demoniac kachina dances, the chief

task of which is to pray for a good crop harvest. In Oraibi, for example, there exists still

today an antelope clan, whose chief task is weather magic.

Whereas the imitative animal dance must be understood in terms of the mimic magic of

hunting culture, the kachina dances, corresponding to cyclic peasant festivals, have a

character entirely of their own which, however, is revealed only at sites far removed from

European culture. This cultic, magical masked dance, with its entreaties focused on inanimate

nature, can be observed in its more or less original form only where the railroads have yet to

penetrate and where—as in the Mold villages—even the veneer of official Catholicism no

longer exists.

The children are taught to regard the kachinas with a deep religious awe. Every child takes

the kachinas for supernatural, terrifying creatures, and the moment of the child's initiation

into the nature of the kachinas, into the society of masked dancers itself, represents the

most important turning point in the education of the Native Americans,

Winter solstice ceremony. The Hopi Ritual Cycle is an annual cycle divided roughly in half. The

period beginning with the winter solstice and lasting until a few weeks past the summer

solstice is distinguished by the frequent appearance of kachinas, masked messenger spirit

beings.

Soyal is a winter solstice ritual designed to turn the sun back in its course. Combined with

this may be a ritual in which medicine is prepared and either drunk or rubbed on the body to

promote health and strength. The first kachina to appear, thereby opening the kachina season,

is Soyal, a shabbily dressed figure who totters along in the movements of an old man. He

makes his way to kivas, placing prayer feathers (paho) and sprinkling cornmeal. Other Soyal

actions include the preparation of prayer feathers for relatives, crops, animals, houses, cars,

and personal well-being.

Hopi Niman Ceremony

The Niman Ceremony, also called the Home Dance, is the last appearance of kachinas at Hopi

before they depart for their homes in the San Francisco Mountains. This early August event

closes the kachina season. The most common masked dancers on this occasion are the Hemis

kachinas, although others may appear. In its solemnity, this kachina dance differs from the

plaza dances that precede it throughout the spring and summer. No clowns are

present.

Kachinas and Kachina Dolls- Their Meaning to the Tribes

Corn Maiden Kachina Doll

Corn woman or maiden who is a figure in many stories. She may appear as a kachina mana, that

is, a female kachina. At Cochiti, for example, Yellow Woman kachina wears a green mask and

has her hair done in butterfly whorls on the sides of her head. She wears an embroidered

ceremonial blanket as a dress and an all-white manta over her shoulders. Yellow Woman tends

to be a stock heroine in many stories, taking on a wide range of identities, including bride,

witch, chiefs daughter, bear woman, and ogress.

Sun Kachina and Corn Maiden Dolls

A despised boy who claims to be the grandson of Paiyatemu, the sun youth kachina, is tested

by his father. As a reward for passing the tests, he is given the power to marry the

daughters—Corn Maidens—of eight rain priests. The powerful songs known by these Corn

Maidens cause so much rain that it floods, and the people retreat to Corn Mountain.

The flood finally stops when the young son and daughter of the village chief are sacrificed.

Dressed in ceremonial costume and carrying great bundles of prayersticks, they step off the

mesa into the flood—the boy to the west, the girl to the east. They become the Boy and Girl

Cliffs of Corn Mountain, the place of a shrine considered to give blessings in conception and

childbirth.

Kokopelli Kachina Doll

The Humpbacked Flute Player who appears widely in rock art and ancient pottery throughout

the southwestern United States. Often humpbacked, carrying a flute, and ithyphallic, this

figure has become a widely used motif on pottery, jewelry, and other Native American items.

Although his origins and the significance of his prehistoric appearances are speculative, he has

contemporary presence as a figure in Hopi stories and as a Hopi kachina, where he is

characterized as a seducer of girls, a bringer of babies, and a hunting tutelary.

Heluta Kachina Doll

Heluta is father of the kachinas, creator of deer; he lives in Shipap. As father of kachinas he

is first to appear at kachina dances, announcing the kachinas to the people by means of signs.

Heluta is a figure in many stories.

Kobictaiya Kachina Doll

These are the powerful spirit beings similar to kachinas. A story tells how it was determined

that they would never know sexual intercourse. The daughter of a war chief dies. Her body is

stolen by witches (kanadyaiya) who revive her in order to seduce her. The Kobictaiya come to

her rescue.

Rather than fight for her, they decide to play a game with the witches. If the witches win,

they will get the girl to use as they desire. If the Kobictaiya win, they get the girl but must

forgo sexual relations forever. The Kobictaiya are the victors.

The Kobictaiya appear in masked personated form only at the winter solstice ceremony,

during which they promote fertility and aid the sick. They live either in the east at the

sunrise or in a crater southeast of Acoma.

Pautiwa- Zuni Chief Kachina Doll

Pautiwa, chief of kachinas, summons people from Zuni to Kachina Village to gamble with the

kachinas. They bring goods with them to stake on the game. The kachinas win, and the six men

who lose are trapped under the floor. Realizing that anyone else who loses to the kachinas will

become trapped also, the people send a young man, despised by all, to gamble with them. They

consider his loss of no consequence. However, the despised young man has allied himselfwith

Spider Woman by giving her an offering. He challenges the kachinas and, with Spider Woman's

help, wins every time. At each loss, one of the kachinas drops beneath the floor. The kachinas

soon stop gambling and pay in deer for their losses. They

Soyok Kachina Doll

A ritualized frightening by horrible-looking kachina figures (Soyok) in an effort to discipline

naughty children. The event occurs during Powamu. Upon a parent's request, several of these

ogre figures appear at the home of the naughty child. They demand impossible tasks of the

children, warning them they will be back to check on them in several days. Of course, when

they return the children have not accomplished the assigned tasks and are usually hiding

somewhere in the house. The parents present the children to account for their actions.

The Soyok kachinas, hideous in appearance and equipped with cleavers and saws, demand that

the child be turned over to be eaten. The parents refuse to release the child, but the process

ends up costing the family all its stores of food. The Soyok kachinas, loaded with food, host a

feast for the community and, it is hoped, the child's behavior improves.

Native American Zuni Kachina Dolls

A group of kachinas who live to the south of Zuni and are the enemies of the kachinas who live

at Kachina Village. The hunting territories of these groups overlap. The Kanaakwe decide to

conceal all the deer by hiding them in their corrals. The kachinas of Kachina Village hunt

without even seeing any game. Learning that the deer have been concealed, they challenge the

Kanaakwe to a fight over hunting rights.

The Kanaakwe string their bows with yucca fiber, while the kachinas string theirs with deer

sinew. When it rains, the deer sinew stretches while the yucca fiber tightens, enabling the

Kanaakwe to be victorious. As a result, the deer belong to the Kanaakwe, who are responsible

for bringing them to the Zuni people, while the kachinas of Kachina Village bring the Zuni

people corn, seed, and other things.

This story is often included in the stories of Zuni Emergence. In some versions the Kanaakwe

are led by a giantess who keeps her heart in a rattle. Other versions account for the

origination of the Ahayuta, the twin warrior sons of the Sun Father (Yatokka taccu), in

response to the Kanaakwe concealing the deer. In some versions, the sons travel to their

father to obtain weapons to kill the giantess leader of the Kanaakwe.

Rain priests are associated with each of the six directions, that is, the four cardinal

directions plus zenith and nadir. They live on the shores of oceans and in springs. They come to

Zuni on the winds in the form of clouds, rainstorms, fog, and dew.

Pautiwa, chief of kachinas, summons people from Zuni to Kachina Village to gamble with the

kachinas. They bring goods with them to stake on the game. The kachinas win, and the six men

who lose are trapped under the floor. Realizing that anyone else who loses to the kachinas will

become trapped also, the people send a young man, despised by all, to gamble with them. They

consider his loss of no consequence. However, the despised young man has allied himself with

Spider Woman by giving her an offering. He challenges the kachinas and, with Spider Woman's

help, wins every time. At each loss, one of the kachinas drops beneath the floor.

The kachinas soon stop gambling and pay in deer for their losses. They tell the people that the

six men they have lost will remain at Kachina Village. The people discover that mist and fog

come from the place where the lost men sit. The men tell the people they have become Rain

Priests. Whenever the people want anything they are to come and make prayer offerings, and

the Rain Priests will help them.

In accounting for the origin of the Rain Priests, this story explains why the men who personify

the Rain Priests go on pilgrimage to the lake under which Kachina Village lies, and why people

go to Kachina Village upon death.

The rites that initiate Pueblo children into their adult religious lives include the revelation

that kachinas are humans wearing masks. This often-disenchanting experience is conjoined

with the demand that initiated youth not reveal this knowledge to the uninitiated. Stories of

what might happen to them if they tell are related to reinforce the importance of keeping

this initiation secret.

The Zuni tell a story set at the time during the flood when the people are living on Corn

Mountain. An initiation is held and the initiates warned against telling the secret. While playing

at making clay figures of kachinas, one youth reveals that the kachinas are the children's

fathers and uncles dressed up in masks. Dangerous kachinas are summoned. They break open

the boy's house where he is hiding, cut off his head and, leaving the body lying in his house,

kick his head all the way to Kachina Village.

Kachina Dolls: Their Meaning

and Tribal Development

Kachina dolls are objects made in human or humanlike

shape, and they are common in Native American ritual,

often referred to in mythology. Perhaps most common

are the great variety of Pueblo kachina dolls. Navajos

carve ritual kachina dolls for secret use in some

healing rites. Native American Iroquois have also

taken to carving similar dolls in the False Face image.

Although sold as objects of art, the spectacular

kachina dolls retain a valued religious role, particularly

in educating children. Hopi Native Americans use

kachina dolls to instruct their children in the ways of

Hopi tradition and belief. Kachina dolls are important

during ceremonies when they are passed out to

children.

and Tribal Development

Kachina dolls are objects made in human or humanlike

shape, and they are common in Native American ritual,

often referred to in mythology. Perhaps most common

are the great variety of Pueblo kachina dolls. Navajos

carve ritual kachina dolls for secret use in some

healing rites. Native American Iroquois have also

taken to carving similar dolls in the False Face image.

Although sold as objects of art, the spectacular

kachina dolls retain a valued religious role, particularly

in educating children. Hopi Native Americans use

kachina dolls to instruct their children in the ways of

Hopi tradition and belief. Kachina dolls are important

during ceremonies when they are passed out to

children.